George Bernard Shaw once said: “A bank lends you an umbrella when the weather’s fine, and takes it away when it rains”. Tunisian banks seem to be no exception to this rule. At least, that’s what the case of Nahrawess Boujaafar suggests, according to owner Habib Bouslama.

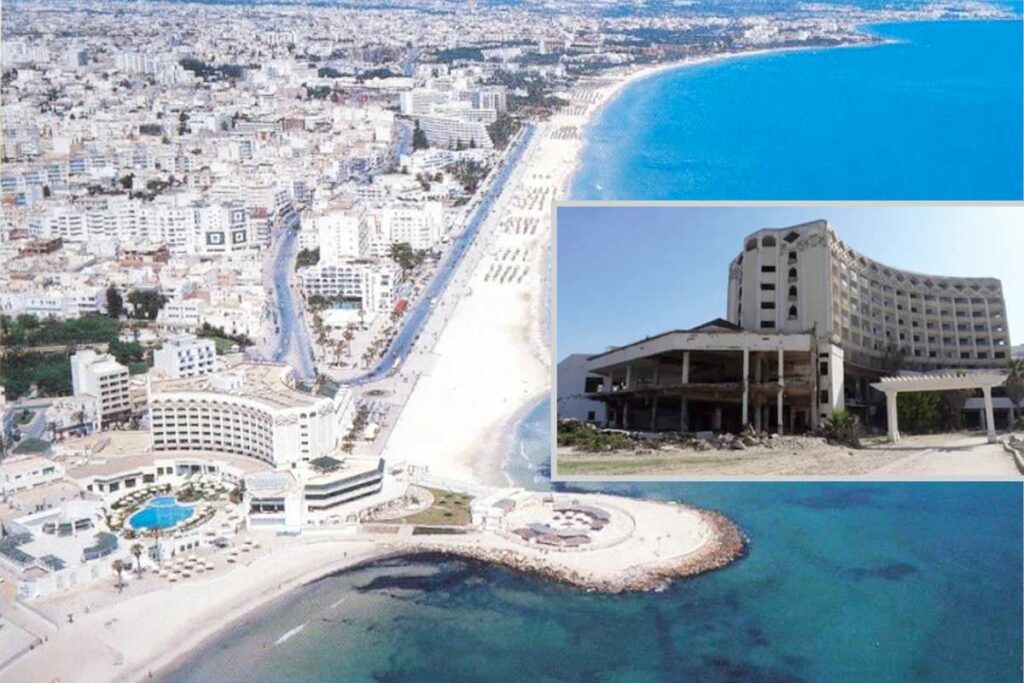

It all began in 2008, when the owner of the Nahrawess Hammamet hotel was selected as the lucky winner of the call for tenders to sell what was then the Abou Nawas Boujaafar, one of Sousse’s finest hotels and a flagship of the Tunisian-Kuwaiti Abou Nawas chain, which was then being dismantled.

On the strength of a financing agreement involving four banks (STB, BNA, BH and Amen Bank), Habib Bouslama was confident and did not hesitate to engage the liability of the company managing his other flourishing unit, the Nahrawess Hammamet. But he was proved wrong.

His descent into hell began just a few months after his commitment. First, the hotel was downgraded to a 3-star rating for its “dilapidated” condition, he says. Then came the reminder of a tax reassessment of 740,000 DT dating back to 2004, which had been omitted from the accounts presented to him at the time of the buyout.

But for him, there was no time for hesitation. He committed part of the credit agreed with two of the banks in his financial package (Amen Bank and BNA) for a total of 13 million dinars. He devoted 1.5 million of this to social reorganization – “because the Boujaafar had been used to house all the unwanted staff of the Abou Nawas chain”, he says today – and then to partial renovation of the establishment.

Once this partial renovation had been undertaken for 7 million dinars, Habib Bouslama thought in 2011 of taking out the remainder of the loan agreed with BNA and Amen Bank. But they “advised” him to turn to the other two banks… Because in the meantime, the tourism sector, due to Islamism, was no longer in the odor of sanctity with political decision-makers and therefore banks.

In 2012, he obtained a meeting with the CEO of STB to be told that “granting this credit would be considered a crime”; to which he replied that “stopping such a project, after spending 7 million dinars, would be even more criminal”. And that’s when the CEO reportedly gave him this reply in the form of a confession: “That’s what they want” (hakka Ihibbou).

Another bank CEO would later tell him that “the tourism situation is not brilliant”. It’s all down to bad luck, then, allowing banks to walk away from their commitments at the whim of political change. At the cost of economic disaster, not only for the hotel purchased (closed and derelict) but also for the guarantor hotel, the Nahrawess Hammamet, which had to assume the repayment of the loans granted – with interest – and even the study commission or commitment commission (1% of the amount of the loan all the same, for a “study” which did not foresee the arrival of the Islamists in power).

Now that it too has been forced to close, the Nahrawess Hammamet is rented out to a third party, a rent that will be used to pay the Sousse hotel’s bills.

A waste estimated by an expert at forty million dinars “in interest and damages”, but which doesn’t seem to worry the decision-makers in the banks or the administration. The Islamists are gone, tourism has resumed growth, and yet the banks’ distrust persists.

The Sousse Center Boujaafar project

As recounted by its main protagonist, this issue seems inextricable. It is less so when you consider the value of the land adjoining the hotel. The owner, Habib Bouslama, is proposing to erect two apartment blocks. The hotel renovation and real estate project, as part of the Sousse Center Boujaafar project, received prior approval from the Tourism Administration in May 2017. In vain, since it remains “classified” by the banks and therefore unbankable for any investor. The ordeal continues.

LM